Former high school quarterback overdosed— and lived to tell his story

Georgian recovered from opioid

addiction amid deadly epidemic

and now works to help others

Graham Skinner woke up in a hotel bathtub that night after experiencing his closest brush with death. The former starting quarterback for Norcross High School had just overdosed on heroin. Years of addiction to painkillers brought him to this point. That much he knew. What he didn’t know was where the others had gone, the ones who had been injecting alongside him. They had abandoned him in that lonely hotel room in Dunwoody back in 2009.

Graham took stock of his situation: While ravaging his body with drugs, he had dropped out of one college, failed out of another one, racked up a long, messy criminal record and alienated himself from his friends and family. There was a warrant out for his arrest.

He didn’t want to die. He felt that was a certainty, if he didn’t make a change. Head throbbing, Graham lifted himself out of the tub. He was about to make a phone call.

The clean-cut son of a software salesman and an executive assistant, Graham grew up in a solidly middle-class, churchgoing family, earning all A’s and B’s, excelling in school sports and participating in a student-athlete leadership program. After he injured his knee and sustained some concussions on the football field, his doctor prescribed hydrocodone and Lortab pain pills. And then his long nightmare began.

"If someone like me can change, if someone like me can get in recovery and stay in long-term recovery, then it’s possible for someone else,” he said. “There is hope. You can make it. You can be successful.”

RELATED: Heroin’s trail of death

RELATED: Driver in heroin-induced crash that killed child gets 30 years

Graham’s descent

Graham believes he is the only person in his family to grapple with addiction. He felt loved as a child. His family attended church on Sundays. His parents treated him well and stuck together. They gave him whatever he wanted, within reason.

But he suffered from low self-esteem as a kid. Sports helped him make friends and feel better about himself. He lettered in baseball and football in high school, becoming the starting quarterback his junior year. But he never thought he was good enough.

Graham traces the roots of his problems to eighth grade at Pinckneyville Middle School, when he started drinking alcohol and smoking marijuana. At his neighborhood pool one day, friends told him they were going to sneak out at night and smoke weed for the first time. Graham remembers thinking he shouldn’t do it. His fear of rejection was so intense that he decided to join them.

In high school, Graham continued smoking pot, even selling it. He figured no one would suspect him, a reputable student from a good family. He fooled everyone.

He injured his left knee and sustained concussions playing football. Doctors prescribed pain pills. He remembers how calm they made him feel. A friend’s mother was prescribed OxyContin after she had surgery. Graham helped himself to her pills, grabbing handfuls at a time.

“The euphoria that came when I took them was like, ‘Oh man, this is an amazing feeling,’” he said. “I realized quickly: ‘I don’t feel bad at all. I feel great when I take these.’”

Then his world collapsed. His mother died suddenly from a stroke when he was 17. Graham was close to his mom. He blamed God for her death and turned his back on his family’s Baptist church. He dived deeper into his addiction, smoking marijuana every day and taking pills at night. OxyContin and Xanax eased his pain.

Graham landed a partial scholarship to play football at North Greenville University in South Carolina. He dropped out after just three weeks, believing he would fail the school’s drug test. He continued abusing OxyContin. It got to the point where he felt worse without it, shaking and sweating.

When he transferred to Georgia Southern University in Statesboro, his addiction came with him. Graham began to rack up charges: driving under the influence of alcohol, minor in possession of alcohol, minor in possession of marijuana and a probation violation. He moved around the state, once living near his older sister in Athens, and getting arrested about 10 times within the span of less than three years. He was charged with disorderly conduct and for having a fake ID. He was sent to jail in Milledgeville for a probation violation and was given a choice: Six months behind bars or rehab.

Graham entered rehab and then went into a halfway house as part of his probation requirements. But he failed a drug test and was kicked out, prompting an arrest warrant for him. He didn’t want to go back to jail, so he hid.

RELATED: As opioid deaths rise, metro Atlanta searches for solutions

RELATED: Atlanta-area governments sue opioid industry amid deadly epidemic

Graham, shown playing for Norcross High School in 2004, injured his left knee and sustained concussions playing football. His injuries led him to painkillers, and an addiction escalated terribly in a few years. AJC file

Graham, shown playing for Norcross High School in 2004, injured his left knee and sustained concussions playing football. His injuries led him to painkillers, and an addiction escalated terribly in a few years. AJC file

Graham during football practice in Norcross in 2004. AJC file

Graham during football practice in Norcross in 2004. AJC file

As a young man with addiction problems, Graham racked up charges. This is his 2009 jail booking photo from Baldwin County. Contributed photo

As a young man with addiction problems, Graham racked up charges. This is his 2009 jail booking photo from Baldwin County. Contributed photo

‘Hard, hard, hard stuff’

Graham’s friends distanced themselves, seeing him as dishonest and dangerous. He stole cash from his father, Art, to buy drugs.

"I had no friends because I would make up some elaborate story about why I needed money. And, ‘Hey, I’ll pay you back.’ And I would never pay them back,” he said. “I could manipulate and talk you into just about anything I needed. And I started believing my own lies, too.”

Initially, Art was in denial about his son’s addiction. He got Graham to see therapists, who diagnosed him only with depression. Art let Graham move back in with him and sent him to three short-term rehab programs. He pulled tens of thousands of dollars out of Graham’s college fund to pay for attorneys as his son kept getting in trouble with the law. Nothing worked.

Then Art attended counseling for parents of addicted children. He told Graham he would help him, but only if he agreed to get treatment. Art no longer let Graham stay with him. He endured sleepless nights, worrying his son would hurt himself or others.

“Hard, hard, hard stuff to do. Hard. Very hard,” Art said. “There would be times when the phone would ring at 2 o’clock in the morning and you would just hope it wasn’t going to be something bad. That happened a lot.”

RELATED: What is fentanyl? 10 things to know about the potentially deadly drug

IN-DEPTH: What the painkillers took: The fentanyl epidemic robs a Georgia family of a daughter and a mother

Hitting rock bottom

Desperate, Graham started showing up at hospitals and faking kidney stones so he could get more pain pills. A doctor in Athens told him the pain could be his appendix threatening to rupture. High on drugs, Graham had it removed so he could get hydrocodone. He tells that story today to illustrate the depth of his addiction.

When pain pills got too expensive, Graham switched to heroin. He rode MARTA to buy it in a notoriously rough area of Atlanta called the Bluff. After injecting the drug for two months, he began to feel sick without it, as if he had the flu. Withdrawal tormented him with diarrhea, nausea and uncontrollable trembling.

Homeless, Graham convinced his grandfather to rent him a room for a week at an extended stay hotel in Dunwoody. He had no job and no money, just a royal blue duffel bag full of his clothes. His hotel room was filthy and smelly.

"I knew what I was doing was wrong. I just could not for the life of me figure out how to stop,” he said. “Dying and not waking up seemed a whole lot better and easier than what I knew was in front of me in trying to change.”

A few others who got kicked out of the halfway house with Graham hung out with him one day in his hotel room, injecting heroin. Graham shot up with them and took Xanax. Sweating profusely, he leaned over the air conditioner in his hotel room so he could feel the cool air on his skin. That is the last thing he remembered.

Graham had passed out before while drinking and using drugs. But this was different. He knew it was serious because of the strange symptoms he experienced — the excessive sweating, the extended blackout, a raging headache and relentless nausea. He wondered if his heroin had been laced with something more powerful, such as fentanyl, an extremely potent painkiller than can be lethal in tiny amounts.

Graham felt pathetic as he looked in the mirror, recognizing how far he had fallen, how much he had lost. Pale with dark circles under his eyes, he had shed about 30 pounds.

"I really don’t want to die,’’ he told himself.

He picked up the phone and called his dad: “Hey, I’m willing to do whatever I have got to do.”

Graham detoxed at his grandfather’s house. Then he turned himself into the authorities and spent more than a month in jail for his probation violation.

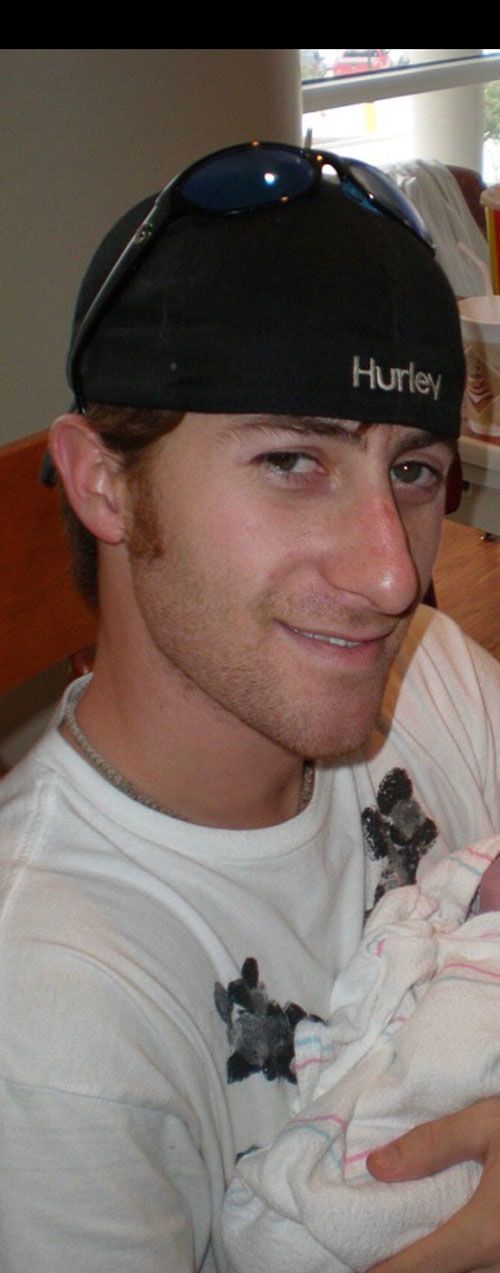

As a young man, Graham had problems with drug addiction. He is high in this 2009 photo, according to his father, Art. Contributed photo

As a young man, Graham had problems with drug addiction. He is high in this 2009 photo, according to his father, Art. Contributed photo

An athlete’s determination

Graham’s father recommended he attend No Longer Bound, a faith-based, 12-month residential treatment program. Located in a neighborhood-like setting in Cumming, the nonprofit does not offer medication-assisted therapy, a form of treatment that uses drugs such as buprenorphine, which can help suppress cravings and withdrawal symptoms. Instead, No Longer Bound focuses on abstinence. And it offers counseling, psychological assessments, random drug screenings, job training and education. Graham said the program worked for him because it connected him with supportive people and helped him rediscover his Christian faith.

Bill Eubanks was finishing treatment for alcoholism there when Graham arrived. He remembers initially perceiving Graham as an “extremely arrogant” jock. His view of Graham improved as he witnessed him draw on the same traits that helped him succeed as an athlete: a strong work ethic, competitiveness and grit. Eubanks saw Graham deal with his grief over his mother’s death and mature.

“The cool thing is those prejudgments I had of him were all proven wrong, completely,” Eubanks said. “Once he got ahold of recovery and what it meant to be living a clean and sober life and got into it 100 percent, it was amazing to see.”

Graham now works at No Longer Bound as a clinical outreach coordinator under the supervision of Eubanks, a clinical administrator there.

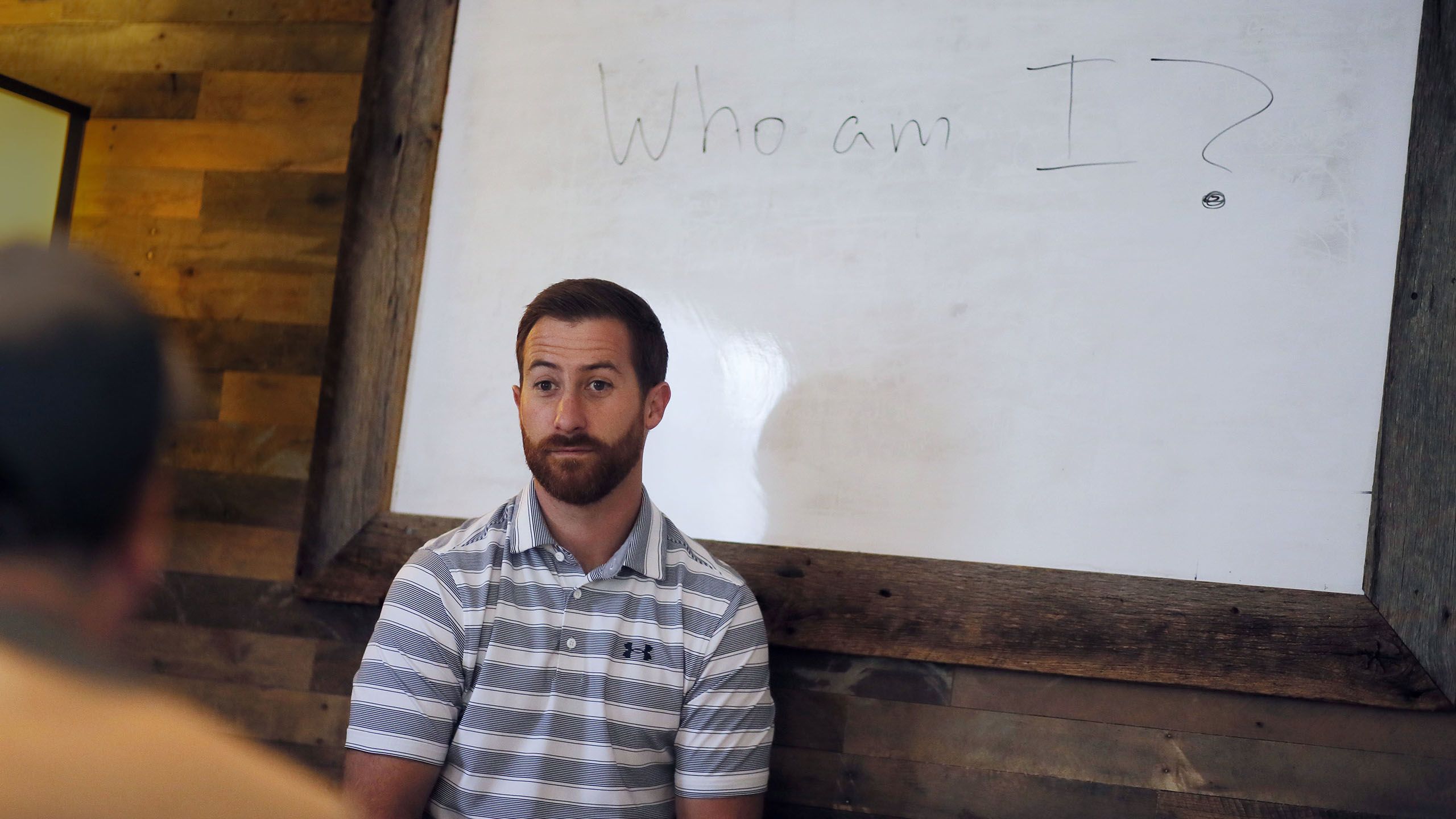

Graham leads a discussion with recovering addicts at No Longer Bound, the treatment center where he works. Treatment center photos by Bob Andres / bandres@ajc.com

Graham leads a discussion with recovering addicts at No Longer Bound, the treatment center where he works. Treatment center photos by Bob Andres / bandres@ajc.com

'I want what he has'

Graham recently led four residents at No Longer Bound through a “check-in” discussion. Two were recovering from alcoholism. The others were rebounding from opioid addictions. They gathered around a low coffee table in a dimly lit office with wood-paneled walls, sharing stories about emotional reunions with relatives. A set of multicolored foam dice — icebreakers for their discussions — sat before them. A resident picked one up and rolled it. It flipped to this question: “What is the most important thing you own?”

“Wow, that has changed a lot,” said Joe, a recovering alcoholic from Macon who asked that his last name not be published for his privacy. “I don’t have a lot of stuff these days, but I would say realistically I feel like the most important thing I own is my own life again. As much as that may be a cheesy answer, that is really what I feel like.”

Graham told Joe he was proud of the progress he had made at No Longer Bound.

“We are not going to leave here healed and done and over with, right? Recovery is a process,” Graham told the group. “We are not done. If anything, we are just getting started.”

Joe sounded grateful — and hopeful.

“I don’t know where things are going to go from here, Graham,” Joe told him. “I’m glad that I am here right now. I am glad that I am not in Macon. I am glad that I have the time that I have got here to continually talk about this and process this.”

Graham brings instant credibility to his job at No Longer Bound, given his own experiences with addiction. Like Joe, Keaton identifies with Graham. Keaton came to No Longer Bound from Gainesville for help after abusing prescription pain pills and becoming addicted to methamphetamine and heroin.

“He used to live the life that we used to live,” Keaton said of Graham. “I see him as a man following God, supporting a family, having children, being a husband, being a leader in this community, helping others, giving back to people. That is why I am willing to listen to him. I look up to him. I want what he has.”

Starting a family

Back and forth on the sidewalk outside his home in Dawsonville, Graham is pushing his two young children in a blue and yellow Little Tikes car. His 3-year-old son, Noble, is gleefully riding in the back, while his 1-year-old daughter, Andie, is grinning in the driver’s seat. As they play, Andie, named after Graham’s mother, stands up on her own for the very first time, delighting Graham.

Graham dreamed about this, about starting a family and owning a home. It’s incredible to him that it has come true after all he has experienced.

His wife, Erin, stands in their manicured front yard, smiling at them. The Birmingham, Ala., native met Graham through a friend who used to work at No Longer Bound. She found Graham genuine, sensitive, a good listener. Soon after they met, Graham told Erin about his recovery from addiction. Months later, he repeated his story for her parents and asked them for permission to marry her. They said yes. The couple married six years ago.

“There was never a sense that I felt — and still to this day have not felt — that I would worry that he would fall back” and relapse, Erin says as the two prepare dinner for their children. “Because of his relationship with the Lord and just the relationships he has with other men and holding each other accountable and just knowing what he went through at No Longer Bound and the hard work that was done on him.”

Speaking publicly about his journey helps Graham with his own recovery. During an opioid epidemic forum this year in the Roswell City Council chambers, he opened up about his journey. Graham is also going back to school, studying to become a certified addiction counselor.

Nine years have passed since the day he overdosed on heroin in that bleak hotel room. Today, when people meet Graham for the first time and hear his harrowing story, they are stunned. Fit, effervescent and engaging, he doesn’t appear as if he has been through hell. He understands when strangers are rendered slack-jawed.

“It’s crazy to me,” he says. “Sometimes I have to remind myself of what my past was.”

Erin (left) and Graham (right) with son Noble in front of their Dawsonville home. Jenna Eason / jenna.eason@coxinc.com

Erin (left) and Graham (right) with son Noble in front of their Dawsonville home. Jenna Eason / jenna.eason@coxinc.com

OVERDOSE EPIDEMIC

In recent years, the number of drug overdoses in Georgia has soared, straining the state’s health care, social service and criminal justice systems. And that doesn’t begin to measure the toll inflicted on family, friends and loved ones of those ravaged by addiction. In a series of stories, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is examining the impact of this alarming trend, what is being done to combat it and the challenge that lies ahead. In August, the AJC reported how dozens of local governments in Georgia are suing the opioid industry in federal court, seeking damages for addiction-related expenses. Today’s article explores a former high school quarterback’s harrowing journey through addiction and his inspiring recovery.

ABOUT THE REPORTER

Jeremy Redmon has written extensively about the nation’s deadly opioid addiction epidemic for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. He also writes about immigration and refugees, and his reporting has taken him to the U.S.-Mexico border, Central America and the Middle East. Redmon is enrolled in the University of Georgia’s Master of Fine Arts program in narrative nonfiction writing.

AJC DECATUR BOOK FESTIVAL

See AJC reporter Jeremy Redmon interview author Beth Macy at the AJC Decatur Book Festival Sunday. Macy will discuss her acclaimed new book about the opioid overdose epidemic, “Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America,” from 3:45-4:30 p.m. at the Marriott Conference Center B in Decatur. The event is free and open to the public. Find more details here: decaturbookfestival.com.

Please confirm the information below before signing in.